Katell Quillévéré • Director

"A humanist adventure"

- VENICE 2016: French filmmaker Katell Quillévéré talks about Heal the Living, which was showcased in the Orizzonti section at Venice and in competition at Toronto

We caught up with Katell Quillévéré to talk about Heal the Living [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Katell Quillévéré

film profile], her third feature following on from Love Like Poison [+see also:

film review

trailer

film profile] (which was shown in Directors’ Fortnight in 2010 and won the Jean Vigo prize) and Suzanne [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Katell Quillévéré

film profile] (which was shown in Critics’ Week at Cannes in 2013 and was nominated for five César awards in 2014). Unveiled in the Horizons section at the 73rd Venice Film Festival, the film has also been selected to compete in the Platform section at Toronto.

Cineuropa: Why did you decide to make a film adaptation of Maylis de Kerangal’s book?

Katell Quillévéré: When I read the book it really moved me, and I felt like there was a strong connection between me and this story on some deeper level, and that I had to make this film. There were also a lot of elements of the book that I thought it would be exciting to portray through film, especially the way the story takes place over 24 hours. Suzanne, my previous film, takes place over 25 years, and I thought this project presented just as an exciting temporal challenge, especially as I like rethinking the way I tell the story with each film, building the plot differently each time. I also had to avoid falling into the trap of ‘racing against the clock’.

How did you develop the unconventional plot of the book, in which the main character is a heart?

I wanted to avoid the pitfall of making an ensemble film with a lot of characters and too little time to form an attachment to any of them. I tried to construct something that’s neither an account of a story about a transplant, nor an ensemble film, but that has the same structure as an ‘epic poem’: the characters take the reins from one another in turn, creating a sort of guiding thread suspended between life and death. The tricky bit was reconstructing this relay through film and making sure that each character only appeared in very few sequences.

How did you broach the inevitably dramatic and emotional aspects of the plot, without falling into the trap of excessive ‘pathos’?

Yes, it was very important that the film didn’t take the audience hostage. That’s why I placed greater focus on the person who’s going to live, on the person who’s going to receive the heart, than the book does. I also worked endlessly on modesty, especially when working with the actors, asking them to show emotion without taking it too far. The rhythm is also very important in stopping the viewer from falling prisoner to their emotions, in letting them breathe before returning to the serious issued, surgical operations that aren’t always easy to watch, etc.

What about the strong realism of the hospital environment?

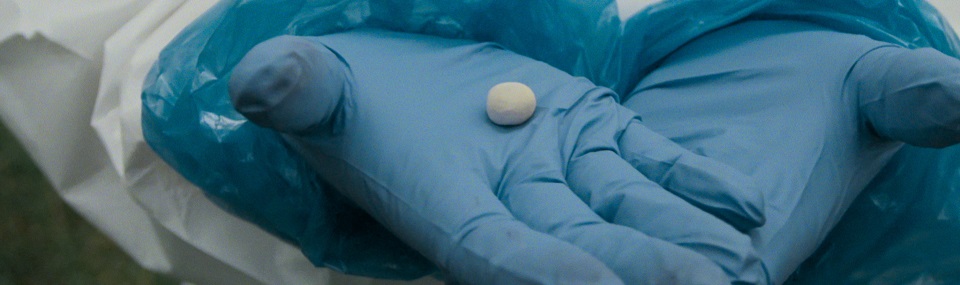

I was struck by the documented aspect of the book, and then became fascinated, as I immersed myself in the hospital environment, by transplants as a sort of scientific experiment. I wanted to portray an organ as we don’t usually get to see it, and to broach it in general terms, so that the relationship we have with our own heart has changed by the end of the film. That was only possible by taking this very raw approach to the organ, this heart that we start seeing as a piece of meat, being sewn and re-sewn, transferred from one body to another. But I also wanted to portray the heart as the nerve centre of all our emotions. More broadly, I think that a film should tread ground we don’t usually tread, with images that can be quite transgressive deep down. The operating theatre is an incredible film location, but these are documented images, not documentary images, as they’re very sophisticated. With the director of photography, we took our inspiration from Cronenberg, from Caravaggio’s paintings, using pretty extreme colours.

The very well-executed surf sequences at the beginning of the film were also a real directorial challenge, were they not?

They were both a headache and an incredible cinematic challenge. We watched hundreds and hundreds of surfing videos to get our heads around the sport, which is also a state of mind, a way of life, with the threat of death hanging over it constantly as it’s very dangerous. We wanted to understand the aesthetics of it, see how we could reinvent surfing’s image, combine it with fiction and tell a story through it. What’s interesting, is the connection with this element, the sea, this sort of matrix that the character is trapped in and could crush him at any moment. There’s a metaphor in the sea because it’s where we all come from: life is born from water. And that’s also why I open the film with it.

Heal the Living is also a film about family, teamwork and the chain of life, is it not?

I thought it would be fascinating to explore the extent to which a transplant is a humanist adventure, and I tried to convey that, as the film questions the link with the eternal. The story unfolds first and foremost at the level of the individual, a family, then a community, that of the hospital, and then society, as in France everyone has the right to a transplant. It’s an adventure that sets society in motion at all levels. A transplant is rooted in the principle of solidarity, and reminds us of just how interlinked human beings are.

(Translated from French)

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.