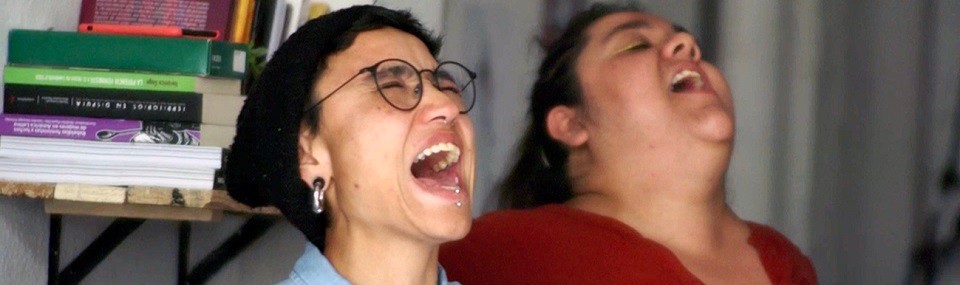

Thomas Arslan • Director

“I prefer a suggestive approach”

- BERLIN 2017: Once again up for an award in Berlin, German filmmaker Thomas Arslan tells us about his latest film, Bright Nights

Together with actors Georg Friedrich and Tristan Göbel and producer Florian Koerner von Gustorf, German screenwriter and director Thomas Arslan gave the international press a few pointers for approaching his most recent feature film, Bright Nights [+see also:

film review

trailer

Q&A: Thomas Arslan

film profile], fresh from its world premiere at the 67th Berlin International Film Festival.

What first prompted you to make this film, which looks at the relationship between a father and his son?

Thomas Arslan: After Gold [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Thomas Arslan

film profile], I wanted my next film to be closer to my own experience, and to take my everyday life as the starting point in a logistical sense as well. I was also keen to look more closely at the relationships between people. Then again, that could be the starting point for every story that has ever been told, and perhaps only a psychologist would really be up to the task.

Why did you choose to set the story in the mountains of northern Norway?

The character of the father is settled in Germany when his father dies; that’s what sets this journey to Norway in motion. The time he spends with his son is not just a holiday, because they are in an extremely remote part of the world. There are no distractions and no amusements, and so they have to deal with one another the entire time. For me, this landscape forms a very particular setting, and that has a tangible influence on the story because the two characters are forced to come to an agreement and try to get along. Also, because they have no pre-established dynamic to fall back on, they need to find a way to talk to one another, and that’s not simple, because each is instinctively inclined to reject the other. From the son’s point of view, his father has been absent for many years and now suddenly he’s back. And of course, to be able to understand someone, you need to be physically present — that’s the first step.

Nature itself has a crucial role in the film.

When I’m putting together a road movie, the way the characters move across the landscape is obviously very important to me, and so I try to give it a real presence in the film — not in a symbolic sense, but as the environment in which the characters interact. In a way, it has to do with the relationships between them — these people who find themselves thrown together in that isolated scenario. It’s completely different to spending time together in a crowded city.

Why is it so difficult for a father to identify with what his child is feeling?

It’s a matter of having empathy for the other person. It’s not all that easy or straightforward to look beyond ourselves and our own preoccupations to really see somebody else on a deep level — and as with all aspects of modern life, the existence of conventional models only makes things more complicated.

The father and his son grow closer together, but at the same time we see the classic dynamic whereby the child is determined not to turn into his parents.

We all try to avoid the mistakes of our parents’ generation, but we realise that things tend to repeat themselves regardless, and in that respect there will always be some fundamental pull that very few of us manage to escape.

In your previous films, the male characters are very often lone wolves. This time, we can detect a slight evolution.

I think that, in this case, the character is a loner who is capable of opening up. Something dramatic happens and that changes him; it compels him to behave in a different way.

Tell us about the character of the grandfather who has just died.

In the main narrative of my films, I don’t like to lay out the backstory through dialogue — I prefer a suggestive approach. I don’t feel the need to reveal every single detail. The viewers need to join the pieces together for themselves, and that’s why the grandfather is only mentioned a few times. In a certain sense, it’s a chain, a repetition.

Why did you opt for such a relaxed pace, with the long sequence shots we see in the film?

I don’t really think about films in terms of fast or slow. That’s too formal a way to look at it, and I don’t work like that at all. I tried to bring the appropriate rhythm to this very particular story, without being bound by general conceptual rules. I think it’s the right speed for this kind of story, and it’s in keeping with the progress of the characters as they move across this space. For example, the sequence where the two characters are travelling through the fog is really quite long, four and a half minutes, but I wanted to convey a real, physical sense of what it is like to be immersed in fog, and a sequence shot seemed like the best way to achieve that.

(Translated from French)

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.