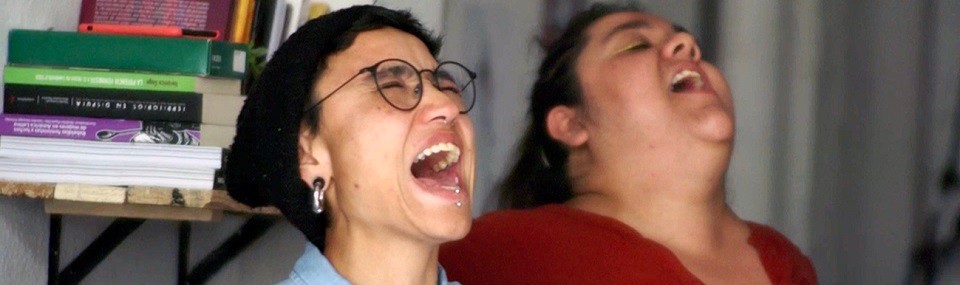

Christian Volckman • Director

"A technological and artistic revolution "

- Interview with a young avant-garde director, a visual explorer, a revelation in the world of animation

Hurled into an impressive media circus for his first feature Renaissance [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Aton Soumache

interview: Christian Volckman

film profile], Christian Volckman dedicated time to give Cineuropa a rapid tour of his sources of inspiration and his approach to animation’s new technologies. A meeting with an impassioned 34 year old of whom we have not heard the last...

Cineuropa: How did you come up with the "motion capture" techniques which so characterise Renaissance?

Christian Volckman: I first saw black-and-white images which used "motion capture" at the Salon Imagina in 1998, tests made by Marc Miance (Attitude Studio). It seemed we were seeing the movements of real actors in a graphic universe that was staggered. I was drawn to it immediately. The cinematic transposition opened up extraordinary perspectives of using my influences such as the American noir films, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and M Le Maudit, and also the Russian experimental films of the 30s. Dziga Vertov, for instance, bowled me over with his madness, his energy and his freedom. Drawing on these influences, which are all part of a chain, motion capture offered me the possibility of modernising them, using what I consider to be the apogee of cinematic emotion: black-and-white, which make the spectators’ subconscious work overtime. It also brings the human dimension into the graphics, the movement and the emotion, which does not exist in traditional animation. On 3D, we first capture the actors’ movements before making the backgrounds and settings, which allows for a great deal of freedom even though "motion capture" does not capture facial expressions (once the frames have been posed, the animators animate the faces). But it will no doubt evolve. A technological and artistic revolution, a wonderful tool, an ally whether you use it with a desire for precision or as a limitless abyss.

What were your preconceptions before making the film?

In my short Maaz, I already explored the themes of a man lost in the city. But meeting with the graphic people, the artists and the architects enriched the proposal. One has to fix some constraints because there is so much freedom, such a potential that it’s like an extension to dreaming: one can imagine everything and make it, with the inherent danger of recreating a dream which is often not very structured. So I decided to only create movements which are possible in reality, that the scenes would concentrate on the actors and that the sets would be used sparingly. It’s almost the inverse of what they did on Star Wars where access to the technology allowed for cities with millions of inhabitants, space ships in every sense... For my film, I had to maintain sober images, both in subject matter and the sets because black-and-white imposes control over where the spectator looks. And if we forget that, we’re not respecting the public. Also, the power of cinema (someone like Hitchcock for example), it’s what remains unsaid, the unconscious aspect, the suggested. I don’t like gratuitous violence like Sin City because culture has other things to offer while still dealing with the complexity of Man.

What was your personal interest in the screenplay written by Matthieu Delaporte and Alexandre de la Patellière

The idea was to push the logic of the obsessions of certain pharmaceutical groups, agribusiness and others who are determined to sell us rejuvenating creams, medicine or genetically modified plants. Behind the economic dimension, we panic about getting old, getting sick, dying, which paradoxically is what being human is all about. If it is pushed to the limits, the logic is frightening. The creams, the Botox, the physical perfection are just the tip of the iceberg. There is a madness at the heart of it all, the refusal of what nature offers us, the refusal of our natural state, which adds anguish about our place in the universe. Philosophical questions arise from all of this and Renaissance takes on the subject by asking what would happen if a means of stopping cellular ageing was found. I am not convinced that it would be a positive thing for Humanity.

How do you view the continuation of your career after such a dazzling debut?

It’s my first feature, I have to master the language of cinema, the techniques before I can let myself tell no matter what kind of story. I haven’t explored everything in black-and-white, but I have arrived at the crossroads of several personal obsessions: painting, graphics, the black-and-white cinema of the beginning of century, film noir. I have certainly got some things out of out my system. For now, I am digesting my six years of work on Renaissance and I am waiting for the public to come.

Would you be attracted to directing a live-action film?

I’d love to, but I would have to know what story to tell. With animation, one can hide behind a certain aesthetic, but it is more difficult with a live-action film even though David Lynch proved it’s possible (with all that symbolism behind it). I would only do it with a very interesting proposal and maybe I’ll take ten years to make another film. I admire Terrence Malick who takes his time which is the opposite to what happens in the current economic climate where we have to produce and consume as fast as possible, allowing no time for reflection.

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.