Erol Mintaş • Director

“Stories are an important part of Kurdish tradition”

- Erol Mintaş speaks to Cineuropa about the central relationship in his film, the tradition of storytelling among Kurds and how the film got financed thanks to interest in the Kurdish community

Turkish director Erol Mintaş, the winner of the Heart of Sarajevo for Best Film for his feature debut, Song of My Mother [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Erol Mintaş

film profile], speaks to Cineuropa about the central relationship in his film, the tradition of storytelling among Kurds and how the film got financed thanks to interest in the Kurdish community.

Cineuropa: Why is the mother-son relationship at the centre of your story?

Erol Mintaş: I am a Kurd who grew up in Turkey in the 1990s, when all of the connections between Kurds and their mother tongue were cut off. For me, my mother was crucial in keeping my native language alive. She was telling me a lot of stories, which is an important part of Kurdish tradition, and maybe that is where I got this urge for storytelling. That is why this relationship is so important to me.

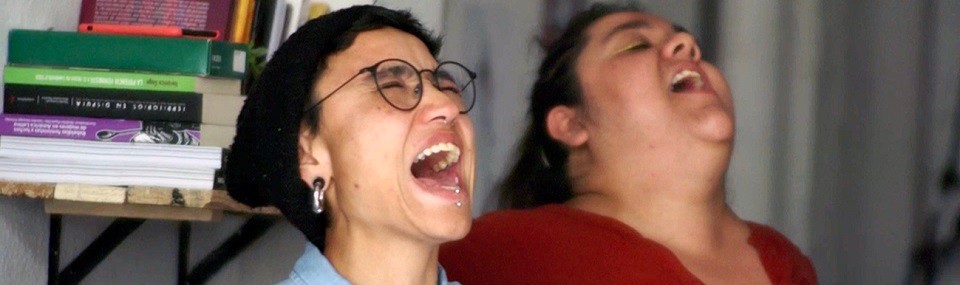

The main character's girlfriend, Zeynep, is an assimilated Kurd – she speaks Turkish instead of Kurdish. What relation is there between young Kurds and their identity? And how does she approach her relationship with Ali?

In the Kurdish community in Turkey, we have two ways of living with being a Kurd. One side fights against assimilation, and they try to keep their culture and language alive. On the other side, because of the fear of violence coming from the state, some people stop using their language. Zeynep belongs to this second wave. Her parents moved from Kurdistan to Istanbul and were afraid that their daughter would have a harder life and suffer if she did not adapt.

Even my parents, when I was a child, would tell me not to speak Kurdish in school or say I was a Kurd. Zeynep speaks Turkish because her parents didn't teach her Kurdish.

In the relationship between Ali and Zeynep, there are a lot of weird things, but Zeynep still wants to keep it going and save it. She is very stubborn about it.

You chose a fantastic non-professional actress to play Nigar, Ali's mother. Where did you find her?

She is the mother of one of my friends. I met her at a conference about the Armenian genocide. She was living in an Armenian neighbourhood, so they invited her to speak about the old times. When I saw her face and her eyes and how expressive she is, I thought she was perfect for the role. At first she didn't accept the offer to act in the film. I tried to convince her for a long time, and I even got her family to try to help me.

As she wouldn't do it, we did a casting to find the right actress for the role, but I kept thinking about her. I told her that if we didn't get her to play and could not make the film in time, I would have to return the money from the Ministry of Culture.

Finally, she was convinced by her cousin, who is the head of their village, that this was an important thing to do for Kurdish language and culture. She ended up behaving like the most professional actress – she was brilliant.

Her character believes that all her friends have moved back to their villages. There must be a lot of yearning for home among displaced Kurds in Turkey.

There are a lot of people like her – not only Kurds, but immigrants from the Black Sea area who had to leave their homes. When I was at university, we had a study group dealing with issues of minority rights, and I met a lot of them. This is where the idea for the film came from.

How did the financing of the film go, and why did you decide to opt for Sarajevo as the place for your world premiere?

The budget was about €300,000, and it came from the Ministry of Culture and two post-production awards, from Cinémas du Monde and 1000 VOLT. It was a tough film to finance, but we had help from the Kurdish community, and some online crowdfunding. Some of the Kurdish businessmen realised that this story is kind of a cause for the whole nation. That way we got a sponsor for transport and catering, which is a big thing.

We thought Sarajevo was perfect for us because of its size, reputation and the possibility for the film to be visible, unlike, for instance, at the Berlinale, where there are just too many films.

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.