Stina Werenfels • Director

"I love films that allow the audience to assess their own feelings"

- We met up with Swiss director Stina Werenfels to talk about her latest film, Dora or the Sexual Neuroses of Our Parents, and its refreshing twist on sexuality and disability

Swiss director Stina Werenfels unveiled her latest movie, Dora or the Sexual Neuroses of Our Parents [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Stina Werenfels

film profile], at this year’s Solothurn Film Festival and has since shown it in the Berlinale’s Panorama Special section, before taking it to the Brussels Film Festival, where it won our very own Cineuropa Prize. We met the filmmaker to talk about the movie, what’s in it and what’s behind it, and how such a topic (sexuality in people with an intellectual disability) can be brought to the silver screen.

Cineuropa: Dora or the Sexual Neuroses of our Parents delves into an interesting yet perplexing topic for the viewer. What made you choose it?

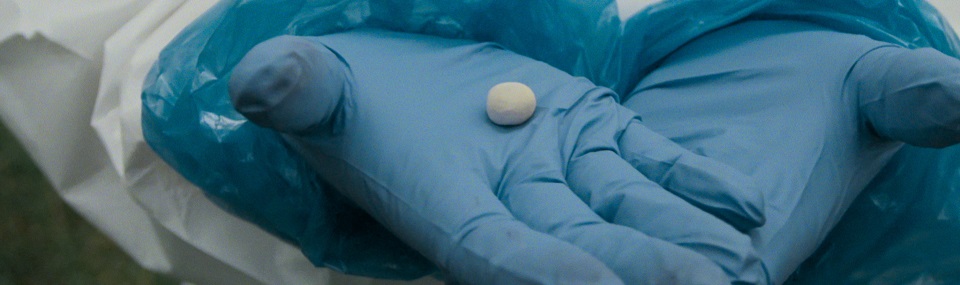

Stina Werenfels: The film is based on the famous piece by Swiss playwright Lukas Bärfuss. I saw it in 2003 and it hit me because of its controversial and ambivalent qualities. It seemed to me that Lukas was cutting through the flesh of our Western society and its hypocrisy. Though we live in liberal, permissive times and though we claim to give equal rights to those with intellectual disabilities, when it comes to sexuality – and moreover to pregnancy – alarm bells ring. The piece allowed me to enter the moral grey area of what is right and what is wrong, what is “normal” and what is not. It also gave me the opportunity to bring in two strong female perspectives on fertility and motherhood.

How did you manage to avoid the conventional, clichéd depiction of intellectual disability in cinema?

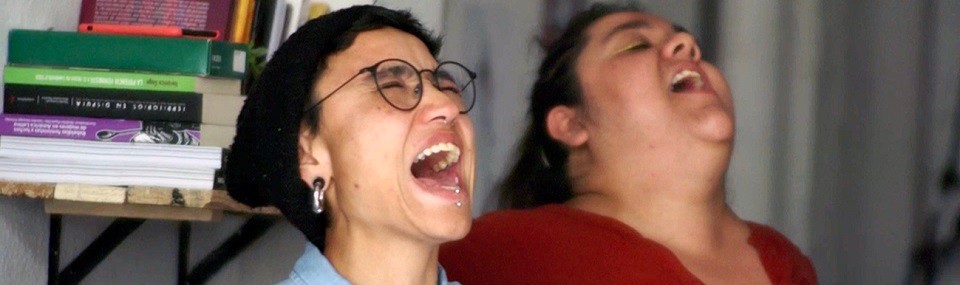

First, it takes a lot of research and immersion in the reality of people with disabilities. A clichéd depiction stems from showing the disabled person from one single angle: disability. This is not only clichéd, but also discriminatory, because any human being features a vast range of characteristics. Disabled people are often shown in films as being “cute” and “heartwarming”. It has almost become a genre… But our Dora is also spoiled, hot-tempered and has an extraordinary lust for life; she can be nasty to her friends and, above all, has got a strong will. This makes her a character, not a diagnosis.

Victoria Schulz gives a stunning performance, but you also worked with actors with intellectual disabilities. Did you at any point consider having one as the lead?

Yes, definitely: authenticity is important. During the casting process, I saw acting students both with and without disabilities. I then became aware of how extremely demanding the part is, since non-disabled actors were especially very hesitant to play the role owing to its physical explicitness. My feeling was that I did not want to force an inexperienced person, whether disabled or not, into a radical performance. That could have become an abusive situation that I absolutely wanted to avoid. Victoria Schulz didn’t only come with her extraordinary talent, but she also immediately shared my artistic view on Dora: she wanted to go far – this is what she is interested in as an artist. As a director, I want to fulfil both sides: to be sincere (and not manipulative!) to the actor and true to the character.

Although it is also sexual, the film is much more psychological than physical – the flesh is quickly replaced by the brain...

I love films that are emotional, erotic, physical and “brainy” at the same time. They allow the audience to assess their own feelings. To me, the success of a film is not measured in numbers, but according to whether it carries forward its questions into our daily lives.

What was it like getting this film made? Was it difficult because of the topic and the approach?

The film took us seven years, from writing it to its Berlinale premiere. Financing was definitely the toughest part. It meant convincing people to give money to a taboo subject without me as the author smoothing off the edges. The script scared the film commissions – yet it was clear that turning it down was more of a gut reaction than a judgement on its quality. But we must also remember that at the time, arthouse film in Switzerland was particularly under siege: I was very active in cultural politics then to help to get things to change.

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.