Nicolas Silhol • Director

"The subject matter of the film scared people"

- KARLOVY VARY 2017: We caught up with French filmmaker Nicolas Silhol to talk about his first feature film, Corporate, which is being shown in competition at Karlovy Vary

After graduating from the Fémis, Nicolas Silhol rose to prominence with his short films Tous les enfants s'appellent Dominique (which was shortlisted for the Oscars in 2010 and won the Grand Prix at Toronto) and L'amour propre (which had a special screening in Critics’ Week at Cannes in 2010 and was shown in competition at Clermont-Ferrand in 2011). His debut feature film, Corporate [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Nicolas Silhol

film profile], which was released in France in April and was a success with audiences and critics alike, is now being shown in competition at the 52nd Karlovy Vary Film Festival (being held from 30 June to 8 July 2017).

Cineuropa: Where did the idea for Corporate come from?

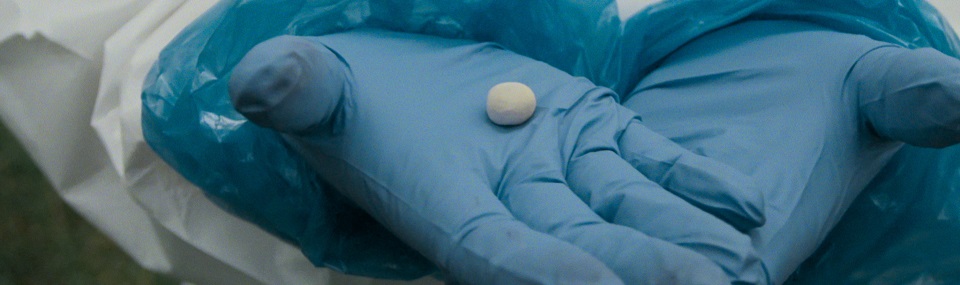

Nicolas Silhol: It all started when I found out about the string of suicides at France Télécom between 2009 and 2010, and I started looking into them with my co-screenwriter Nicolas Fleureau. We found out about these methods of management by terror, and what really stood out and shocked us was the attitude of the then director of the company, who talked about "this trend in suicide" that had to be brought to a stop. What we were interested in was the issue of liability, because there was this sort of trivialisation of suffering in the workplace, including its most dramatic consequences, as if it were the system’s fault, as if there were an economic war raging that left behind victims, simple as. A macabre practice took hold at France Télécom, which was more or less relayed by the media, with 30, then 40, then 50 suicides coming to light and being presented a bit like inevitable tragedies. The question we asked ourselves was whether there were people responsible for developing and putting these systems of management into practice.

The plot begins quite fittingly with a suicide. How did you build the narrative structure?

We wanted to focus on the way in which the main character faces up to the consequences of this trigger event. It’s the point of departure for her process of transformation. After she lets something slip at the beginning of the film when she is cornered and pressed for answers, she first reacts by going into denial, treating it as a taboo and keeping quiet about it, before entering a stage of acceptance and finally recognising things for the way they are.

So the main character is pretty ambiguous, locked into a system it’s difficult to extract yourself from when you benefit from it.

Absolutely. She really embodies the system. What seemed rather pivotal to me, in her dilemma, is that to turn against the system, she must turn against herself. To some extent, she must mourn the woman she once was.

How did you work on the suspense and the visuals?

My favourite device in film is shots and reverse shots, and it’s no coincidence that I chose to make a film that mainly plays out through scenes of confrontation and dialogue. From a narrative and dramatic point of view, we tried to put ourselves in a crisis management situation: there’s an urgency and a rhythm to the film that ensures the characters, especially Emilie, are always moving. There’s also this stylistic device that you find in certain American "walk and talk" series. Furthermore, we wanted to make the most of the corporate setting, the open spaces, corridors, glass partitions, playing with points of view and perspectives, dismantling the sound and images. One thing we really wanted to do with the scenery was to play with the relationship between inside and outside. Everything in the world of business is very clean cut, with sharp frames that isolate the characters and create lines of tension, whilst outside is characterised by a style more anchored in reality, which is a lot less slick and features a lot of sequences with handheld camera shots.

Was the film easy to find funding for?

It was quite difficult, as we realised that this was a sensitive issue, taboo even, and that some partners didn’t want to get involved because they wouldn’t have complete control over the film’s content. This was the case for TV channels, which were pretty timid about the whole thing, and then for the companies we wanted to use for filming. We spent a long time looking with the support of the Rhône-Alpes region and no one allowed us to film on their premises, which forced us to hire sets and fill them. The subject matter of the film scared people. But we had partners who, despite being very few, were very supportive. This is a film that sinks its teeth into a social issue and tries to do so in the most accurate and meticulous way possible. And the French release of the film, with the very strong word-of-mouth promotion it received and the multiple debates it sparked, showed us how important it was for lots of people to talk about this.

(Translated from French)

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.