Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne • Directors

"For us, cinema is a type of living matter"

- The Dardennes take a look back at their filmography as part of the programme offered by the Cinema and Audiovisual Centre of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation, celebrating 50 years of Belgian cinema

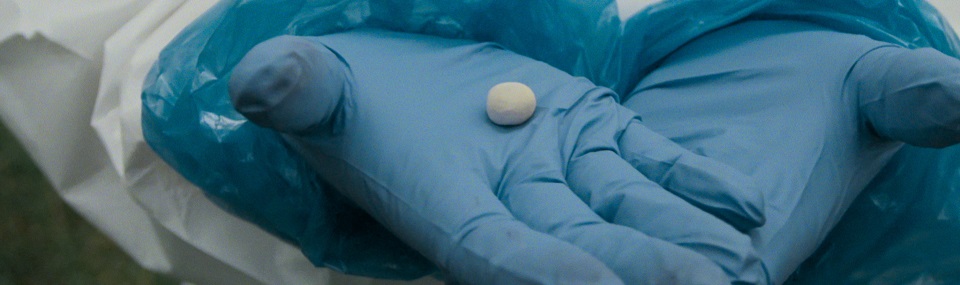

On Tuesday 14 November, a fascinating interview took place with the Dardenne brothers and Fabrizio Rongione in Brussels, where a restored version of the film Rosetta – which won them their first Palme d’Or – was presented during a retrospective of their work and as part of a programme celebrating 50 years of Belgian cinema at the Cinema and Audiovisual Centre of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation. This interview, conducted by Nicolas Gilson, allowed us to take another look at a film that holds a key place in world cinema, as well as re-familiarising ourselves with the filmography of the Dardennes themselves.

Is there a genuine desire to break with classicism in your films?

Luc Dardenne: There were two fundamental things that were essential to the aesthetic of the film in our minds. Firstly, Rosetta has no idea what tomorrow will bring. She lives in the moment because she doesn’t know what will happen in the future. We wanted the viewers to think that the characters’ reactions depended entirely on what was happening to Rosetta at any given time, as if it were all happening live on screen. Rosetta is a long way away from a Romanesque film where the story builds little by little and where the viewer can guess the ending, more or less. Secondly, the camera needed to be slightly behind on Rosetta. The audience couldn’t know what she was going to do. They could understand her motivations, but she remained unpredictable nonetheless. We had to work with the cameraman to convey that feeling of unpredictability.

The paradox is that despite what appears to be a hyper reality, the camera has a real presence in the film. You can really feel it.

Jean-Pierre Dardenne: Yes, of course, you can feel the camera, but I hope it doesn’t take centre stage. The aim was to avoid any form of Mannerism. It’s fine to create sensations and feelings through the positioning of the camera, but we don’t want to end up simply demonstrating the process of staging a film. By being “in the wrong place”, being behind and through the sensation of looking over someone’s shoulder, the camera can see things and allows Rosetta and Riquet to exist in all their depth. We try to ensure that our characters are more than just mere faces.

LD: The closing shot of the film is of Rosetta’s face. Some of those who read the script were very worried. They thought to themselves, “No one is going to like this girl”. But you can’t help but end up liking Rosetta, even if she’s not nice, and it’s all because of her face. It’s what makes her likeable as time goes by. We didn’t improvise when it came to filming, but we did film in sequence shots, so it’s almost a kind of highly constructed improvisation. What with the camera, the crew, the person framing the scene, it can get particularly tense, such as when the timing of the focus is out. Ultimately this tension contributes a great deal to the film.

How do you maintain spontaneity in spite of all the rehearsals? Does filming in chronological order help?

LD: There’s not always an explanation for these things. We rehearse a lot beforehand, especially for this film which was actually very physical. Rosetta gesticulates a lot, she moves around a lot. When you film someone falling, you can rehearse it as much as you like, it’s always like it’s the first time.

J-P D: Our shots are long so you don’t see the same thing twice between takes. We don’t ever set up marks for the actors, either in rehearsals or during filming. The cameraman knows where he needs to be, but you never really get the same thing twice, there’s a constant tension. Rosetta is a very physical film; the body plays a huge role in it. I would say that we try to be right in amongst things, to be present, so that the viewer can feel the depth of the characters and can feel a human presence. We do have certain ideas, but we expect things to take shape through hard work. For us, cinema is a type of living matter, and there comes a point where you feel like it’s coming to life.

LD: When we start to feel like what we’re shooting is a copy of something else, or that we’re thinking about another film, or that ours is becoming a replica, we stop. That feeling is something that you pick up on fairly quickly. While certain movies play on references to other films, many movies simply film themselves filming, and the subject itself just isn’t there. The movie is a mere echo of the subject. Our aim is to give the feeling that what we are filming, what we are seeing, is happening now, in the present, and that it is coming into being in the confines of that very shot. We want to give the impression that we just happened to be there.

J-P D: That’s why films are only as good as what you make them during the shoot...

(Translated from French)

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.