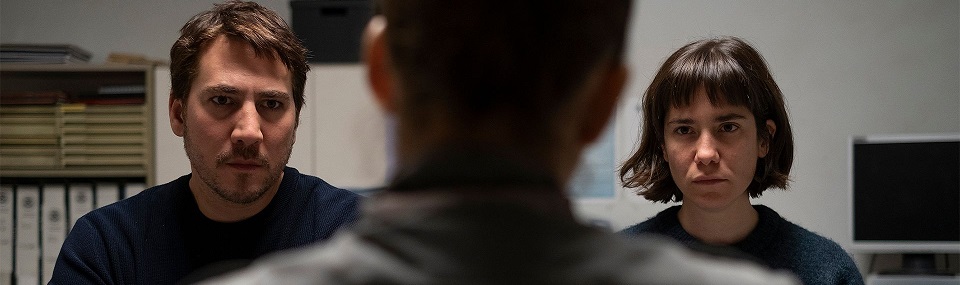

BERLINALE 2011 Competition / Germany

Uncertain wind of change in If Not Us, Who

When someone suggested to German director Andres Veiel that he make a film about Bernward Vesper – who was known during his lifetime as the son of Nazi writer Will Vesper and the lover of Gudrun Ensslin before she got involved with Andreas Baader, then after his death (by suicide, naturally, in the spirit of the times) as author of "The Journey" – Veiel says he refused at first, for he felt this story had already been told. Presented in competition at theBerlin Film Festival, If Not Us, Who [+see also:

trailer

film profile] leaves somewhat the same impression, thematically and visually: it is a well-made film and superbly acted (by August Diehl, Lena Lauzemis and Alexander Fehling, this year’s German Shooting Star, entirely convincing in the role of Baader) but it doesn’t avoid the pitfall of the historical-biographical genre, which rarely contributes anything new to cinema or History.

The beginning, with its very literary angle, is nonetheless promising. Few films have yet tackled the German population’s problematic relationship with the literature of the Third Reich, the necessity of separating art and History. This is the task undertaken by young Vesper (born because Hitler wanted people to procreate, his mother tells him, in a revelation that deeply traumatises him) and Ensslin (herself from a Catholic family who, without going quite as far, didn’t reject Nazism either): whilst re-publishing his father’s work (with the help of brief articles penned by Gudrun for the far-right press!), he also praises novels that conservatives consider blasphemous (that’s what makes it literature).

Later on, the publishing house he runs with his companion (over the course of an intense love affair that tries to be different and free but doesn’t survive these conditions well) starts focusing on militant books while the couple become increasingly left-wing.

In this description, we can already make out the many contradictions on which the protagonists’ lives hinge, contradictions that also echo the confused reasons behind terrorist acts and which Veiel effectively details: the contradictions between their social backgrounds and their political objectives, between strength and weakness, between personal reasons (for example sexual) and common cause. The latter two antagonisms are particularly evident in the character of Ensslin, who changes from a young, Catholic-born intellectual in love, to an admirer of Kennedy then a "Medea" (according to Veiel) who is apparently indifferent (except towards Baader) to those around her (including the son she had with Vesper) because the urgent matters are elsewhere, in Vietnam for example.

Unfortunately, while period documents remind us of the time order of events like the nuclear bomb, the Nuremberg trials and the Cuban missile crisis, the film gives up on books and the paradoxes of the era to get radical and, in the process, firmly returns to the beaten track with the arrival of Baader. All the same, the film’s coda focuses on the character of Vesper, to whom it does, after all, owe its interesting beginning before it relegated him, as History did, to a secondary role.

(Translated from French)

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.