CANNES 2010 Directors’ Fortnight

Dream death of angels in Young Girls In Black

In Jean-Paul Civeyrac’s Young Girls In Black [+see also:

trailer

film profile], the protagonists are not gloomy because they think it’s fashionable, this is clear right from the film’s opening moments. They’re mourning their lost faith in life in a world full of unemployment, exploitation and loneliness; they’re mourning themselves, for they are haunted by the idea of death as an answer to the fact they no longer "want anything".

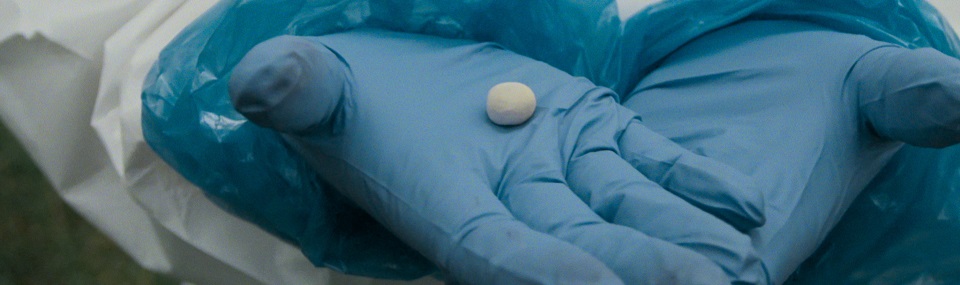

This is what Noémie claims at least. Despite the fact she has family around her, is a gifted musician and produces good schoolwork, she is unequivocally and coldly (she never cries) determined to die. She has attempted it and will try again, and makes no secret of this, either in front of her mother, who is overwhelmed by events, or in front of her class – and if she denies it afterwards, it’s only to ensure nobody stands in her way.

In Priscilla’s case, it’s a bit different. She has more obvious family and academic problems and craves an attention she no longer gets from the boyfriend she says she is passionately in love with at the beginning ("I’m a drag", she says). However, she is clearly the impressionable and weak (she cries) element in the relationship of interdependence that she and Noémie cultivate, forehead against forehead, looking into each other’s eyes, like two sad angels.

Depression, defiance, the death-wish’s power of suggestion; absolute thirst for and romanticisation of suicide pacts between couples like that of German writer Heinrich Von Kleist; disgust at a world that "pretends" and at already being "like them"; an effect of the moon; passing despair at an age when one can be tempted to stupidly and impulsively go beyond the point of no return, "before changing one’s mind" (insists Priscilla): the whole range of motivations for teenage suicide is looked at. The film is indeed the fruit of research into a pet subject of the director, who for ten years collected articles on the theme of juvenile double-suicide, always involving women, earning him compliments from the section’s delegate general, Frédéric Boyer, for the film’s hyperrealism combined with Hollywood-style melodrama (a comment that Civeyrac found flattering, his favourite filmmaker being Minelli).

In the same way, the adults set out the many reasons for not giving in to an unease they see as futile, from the naive "but you’re so pretty" to the grandmother’s reassurance that "there are always some things that go right, little girl", the cousin’s scornful "shut up with your Halloween face" and the ironic "the world’s rotten, right?" from the policeman who arrests the girls for vandalism.

Indeed, Noémie and Priscilla often seem totally indifferent to the consequences of what they’re doing. Sometimes, however, we notice actions typical of those who are attached to life – moreover, Civeyrac remarked at the press conference on the Croisette that the girls’ desire for death is linked to "an incandescent relationship with life". Indeed, we wonder about this. The film plunges viewers into an anxious waiting for a foretold fatal act and this tension is its greatest achievement.

(Translated from French)

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.